Wayward Mind Guide (001): 10 Signs of Moral Injury

Naming the Wound & Building Spiritual Strength When the Soul Breaks Before the Body

The Warrior Identity & the Cost of Not Naming the Wound

There’s a moment from early in my career that still stays with me.

As a hand-selected analyst for a new mission, I found myself in a training center, the low hum of electronics and the weight of silence pressing in on me. The room was dark, illuminated only by the glow of screens, and I felt the eyes of seasoned operators on my back, waiting, judging.

It was not just about speed; clarity was critical. In the middle of the commotion, I remember a specific moment: my fingers hovered over the keyboard, the cursor blinking impatiently, eyes glued to the screen, a singular detail eluding me as I rushed to complete my task before the deadline. It took more than technical skill to ignore the rising panic and focus. I had to communicate what truly mattered quickly, directly, with confidence, because lives depended on it (at least in this training scenario).

After completing my brief, I thought I had done well. As I stepped away, the instructor, a retired service member, leaned in close.

He didn’t whisper.

He didn’t correct.

He didn’t hold back.

“If you’re going to talk about it—BE ABOUT IT.”

I froze. Shame landed, quick and heavy.

Then came anger, all of it turned inward.

Confusion followed.

I wondered what I’d missed and why my effort fell short.

Disgust crept in, too. I felt like I’d failed my own standards.

Back then, I didn’t even have the words for what I was feeling. All I knew was the impact it left.

What I had failed to do in that moment was simple. I forgot to add visual representations to the words I put on paper, well...slides. I talked around the threat instead of naming it. I put way too much data. Trying to cram thousands of ideas into the least amount of information. I described it without labeling it. I analyzed it without making it clear to others.

At that point, I didn’t have the strength or the language to make sense of what was happening inside.

I left that room and walked to the smoke pit carrying shame, guilt, and the sense that I’d let down the mission and myself. Even though it was only a training mission.

Years later, I finally got it. As the “If you are going to talk about it, be about” screamed through the void of my mind back to the front, as I was analyzing my entire life and trying to explain to myself what was going on.

It hit.

If you can’t name it, you can’t heal it.

And I’ll be honest, writing this, I can feel unnamed hurt rising in me too. I have to stop, breathe, and give quiet pain a voice before I can move forward. That pause is learned, and is part of taking ownership of my own journey.

What we cannot name, we cannot carry.

What we cannot separate, we cannot understand.

And what we cannot understand, we end up coping with in ways that hurt us.

Emotional clarity is the first act of strength.

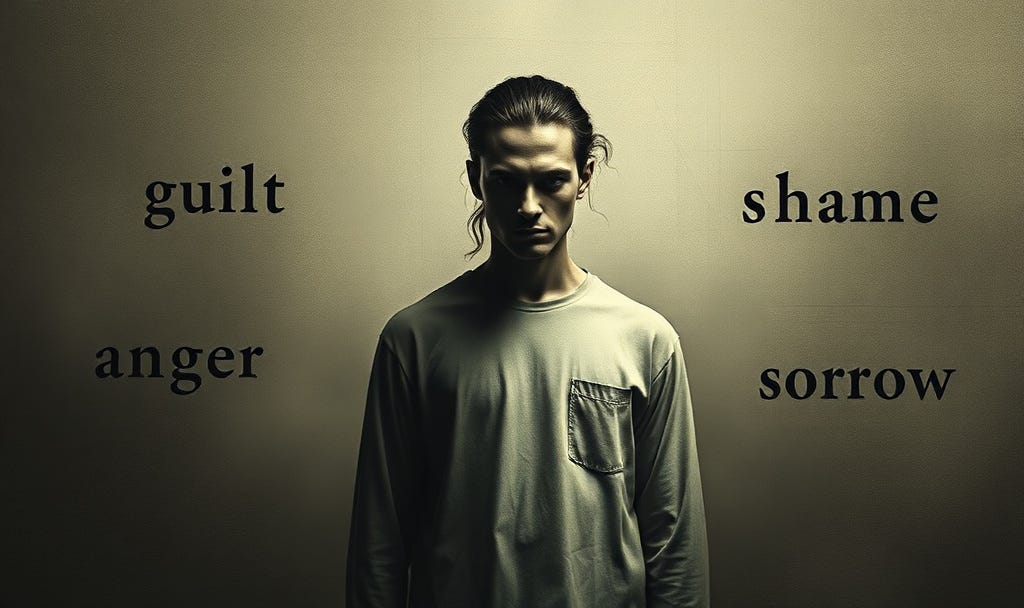

It helps us call each feeling by its true name, to sort guilt from shame, anger from sorrow, disgust from remorse. When we can distinguish them with precision, we can finally carry them. Not as one overwhelming storm, but as individual truths we can face one at a time. And with help and community.

Most coping strategies I see in veterans and first responders aren’t about weakness. They’re just ways to dodge or numb pain that doesn’t have a name yet. I’ve experienced them all.

Substance abuse becomes a way to silence guilt.

Anger becomes a shield to hide shame.

Isolation becomes a cave to avoid the fear of being seen.

Self-destruction becomes moral logic when you believe you deserve punishment.

These aren’t character flaws. They’re survival moves people make when pain has no words.

Of course, you did what you could. This simple truth can soften the harshness of shame, offering a gentle reminder that in moments of struggle, self-compassion is not only deserved but necessary.

That’s why naming your emotions matters.

That’s why spiritual readiness matters too.

That’s why having a moral vocabulary isn’t optional. It’s your armor.

Without it, you’re left trying to navigate your own mess with no map, no tools.

The Limits of Language & the First Step of Moral Repair

The hard part about moral injury is that the pain goes deeper than any words you have for it. It’s not just a mental wound, but one that also manifests in the body. You might feel a heavy sense that something’s wrong inside, perhaps accompanied by a clenched jaw or a tightening in your chest, but you can’t put it into words.

You might say:

“I messed up.”

“I should’ve done more.”

“I failed.”

But what you’re really carrying is a tangled knot of things like:

Guilt (“I did wrong.”)

Shame (“I am wrong.”)

Anger (often at yourself, sometimes at others)

Sorrow (for who was lost, or the part of you that died)

Remorse (a moral desire to repair what cannot be undone)

Disgust (at the actions, the system, or yourself)

Contempt (especially toward those who betrayed what’s right).

Naming emotions isn’t just a surface exercise. It’s the foundation for healing moral injury.

Naming what hurts is a form of spiritual strength and its where moral repair starts. If I could go back to that training moment, I wouldn’t change the lesson.

I’d change how I responded. I wouldn’t punish myself for it.

I’d call out the shame for what it was.

I’d acknowledge the anger directly.

I’d let myself feel the sorrow instead of stuffing it down.

I’d look for clarity rather than hide.

I’d build strength by admitting what happened.

Not just for that training moment, but for every experience like it.

That’s what spiritual readiness is: the ability to face moral challenges with a clear conscience and steady emotions.

It looks like calm assurance when you’re tested,

sounds like a voice grounded in your values,

and feels like inner peace even when everything around you is chaotic.

You can only fix what you’re willing to name.

Unlike PTSD, which is driven by fear and hyper vigilance, moral injury is driven by guilt, shame, and betrayal. It isn’t a mental disorder; it’s a human response to having your ethical compass shattered.

PTSD makes you fear danger.

Moral injury makes you doubt goodness.

It’s the invisible wound that changes how you see yourself, others, and the world.

There’s no scar to point to, which is why moral injury is often called an “unseen wound.” Veterans know this pain well, but they’re far from alone. First responders, medical professionals, social workers, law enforcement officers, and survivors of abuse or betrayal carry it too. Anyone forced into impossible choices, or betrayed when they needed trust most, can be injured this way.

Naming the emotions of moral injury is the first step in healing. Often, others notice the shift before you do. A friend once pulled me aside after watching me go quiet in a room where I used to lead the conversation. His simple question, “Are you okay?”revealed how much I had withdrawn without realizing it.

Moral injury doesn’t discriminate. If you see yourself or someone you love in the signs that follow, know this: you are not alone, and healing is possible.

10 Signs You Have Moral Injury

Let’s now connect what we know about naming emotions and moral wounds with their tangible effects. Identifying these signs is crucial in recognizing and addressing moral injury. Here are 10 signs you have moral injury:

1. “I did a bad thing.”

This thought loops in your mind, weighing you down with guilt. Maybe you followed an order or made a split-second choice that violated your own morals. Now, you can’t stop replaying it. Every time you close your eyes, you see that moment, and you judge yourself harshly. Emotionally, this feels like deep remorse and regret; you’re convinced that because you did something bad, you are bad. You might catch yourself avoiding happiness or punishing yourself in small ways, as if you don’t deserve to feel okay. Behaviorally, you withdraw or grow quiet, reluctant to talk about what happened. You carry the burden in silence, perhaps hoping you can somehow atone for it alone. This is the guilt of moral injury: a constant inner voice saying “I was wrong, I’m the villain”, even if rationally you know you had no perfect options. That guilt may not fade with time; if untreated, unacknowledged, unnamed, it can fester into self-hatred.

2. “I should have done more.”

Moral injury isn’t only about what you did. It can stem from what you failed to do. You might be haunted by the feeling that you didn’t do enough to prevent a tragedy or save someone. Perhaps a comrade or patient died under your watch, and you believe their blood is on your hands because you imagine you could have somehow changed the outcome. Or maybe you provided overwatch, far removed from the conflict, and didn’t see something that ended up causing a death you couldn’t control. This sign shows up as persistent second-guessing and self-blame. Emotionally, it’s a mix of guilt and sorrow: “I let them down. I failed my duty.” You replay all the “if only I had…” scenarios in your head. Behaviorally, you might obsessively read reports or news about the incident, searching for what you missed, or become overly responsible in other areas of life to compensate. This relentless self-criticism erodes your self-confidence. You struggle to forgive yourself for being imperfectly human. In truth, no one can save everyone, but moral injury convinces you that you are at fault for every loss. The weight of that responsibility can be crushing.

3. “Nothing matters anymore.”

One of the most soul-crushing signs of moral injury is a profound loss of meaning. The beliefs and values that once guided you now feel hollow. Maybe you went to war believing in honor and country, or you took an oath as a medic to save lives, only to have those ideals shattered by what you saw or did. Now, everything feels pointless. Emotionally, this manifests as numb despair or a sense of emptiness. Why bother trying? you think, when the world seems so cruel and corrupt. You might notice you’ve lost interest in things you used to love; hobbies, friendships, or ambitions fall away because that spark of purpose has died. Behaviorally, this can look like apathy: going through the motions at work or at home, but without heart. Some days, you might not even get out of bed. In darker moments, you may even find yourself wondering if life is worth living at all. This isn’t classic clinical depression (while depression symptoms could be at play); it’s born from disillusionment. It’s the feeling that the moral order of the universe is broken, so what’s the point? However, remember that this void can also be the soil where new meaning takes root, however tentatively. If you’re experiencing this, know that it’s a common response to moral injury. Your worldview has been upended, and hope feels lost. Recognizing this feeling is important because it’s telling you how desperately you yearn for things to matter again.

4. “They betrayed us.”

Moral injury often comes with betrayal. Perhaps those above you, military commanders, government leaders, department heads, made decisions that violated the moral contract you thought you shared. They might have sent you on an unjust mission, covered up wrongdoing, or broken promises to take care of you and your peers. The result is a seething sense of betrayal and anger. “We did everything they asked, and they sold us out,” you think. Emotionally, this sign feels like righteous anger mixed with hurt. The anger can flare up unexpectedly: you might find yourself ranting about “the system” or feeling a spike of rage at the mention of certain leaders or institutions. It’s not just anger, though; it’s a hollow disappointment, a loss of faith in the very people or principles you once trusted. Behaviorally, betrayal can make you cynical and disengaged. You stop putting effort into your work (quiet quitting) because why bother when leadership has no integrity? You distance yourself from former comrades or organizations, not because of what they did, but because the betrayal has poisoned your ability to trust anyone in authority. This sign is essentially a shattered trust: the understanding that those who were supposed to protect what’s right did wrong instead. It leaves you feeling adrift and furious, like a soldier without a cause, carrying an anger that doesn’t know where to go.

5. “Who am I now?”

When moral injury strikes, it doesn’t just hurt your feelings, but shakes your identity. You look in the mirror and hardly recognize the person staring back at you. You might have once been confident in your moral code: I’m a good cop, a good sailor, a good nurse. But after what happened, you’re not so sure. This sign is the identity crisis that moral injury triggers. Emotionally, you feel lost and disconnected from your former self. You may question the values you grew up with, or the faith you once had, whether in God, country, or humanity. One day, you were clear about your purpose; the next, you’re asking, “What kind of person am I, if I could be part of that?” It’s a deep confusion in which your past, present, and future selves no longer line up. Behaviorally, this might lead you to withdraw from roles or communities that once defined you. For example, a veteran might avoid wearing the uniform or attending unit reunions because it just doesn’t fit who they believe they are now. You might also swing to the other extreme, making drastic life changes (changing careers, leaving relationships, etc.) in an attempt to find a new identity that makes sense. Underneath, there’s a grief for the person you used to be. This “identity collapse” is a hallmark of moral injury: your moral compass spun so hard it lost direction, and with it, you lost your anchor of who you are. Does this sound familiar to those of you who have transitioned out of the military?

6. “I feel nothing.”

A chilling sign of moral injury is emotional numbness. After so much pain and inner turmoil, at some point, your mind might decide to just shut it all off. You wake up and feel… nothing. The things that used to make you laugh or cry don’t get a reaction now. It’s as if your heart has gone cold. Emotionally, this numbness is a protective shield over deep hurt. You’ve been through moral hell, and feeling anything—good or bad—has become difficult. Loved ones might say you seem distant or that you’ve “changed.” Inside, you might worry that you’ve lost your humanity because you can’t connect or care like you used to. Behaviorally, emotional numbness looks like withdrawal and detachment. You avoid social situations because you’re tired of pretending to feel what you don’t. At family gatherings, you force a smile, but you’re not really there. Maybe you engage in risky or self-destructive behavior (drinking too much, reckless driving) just to feel something, or conversely, you avoid any situation that could stir emotions because you’re afraid of what might come out. This numbness is an armor—the result of too much trauma to your conscience. It’s your mind’s way of saying, “I can’t handle any more.” While it might protect you in the short term, it also cuts you off from healing. Recognizing “I feel nothing” as a sign of moral injury is important because it validates that you’re not cold-hearted—you’re hurt. And with time and support, feeling can return.

7. “I keep reliving it.”

Moral injury can trap you in a loop of intrusive memories. Day after day, and especially at night, it comes back. The moment you wish you could undo, the scene you can’t unsee. You might be grocery shopping or trying to fall asleep, and suddenly you’re back in that moment: the checkpoint, the operations floor, the console, the operating room, the back alley; wherever your soul was scarred. Emotionally, this is torment. You feel haunted and on edge, dreading the next flashback or nightmare. It’s similar to PTSD in that the past keeps invading the present, but what you’re reliving isn’t just the fear, but the moral weight of the memory. You don’t just remember what happened; you remember what you did or didn’t do, and it churns your guilt and shame anew each time. Behaviorally, you might go out of your way to avoid anything that triggers these memories. You steer clear of certain movies or news stories, avoid specific places or people connected to the event, or numb yourself with substances to escape your own thoughts. You might also find yourself compulsively talking about it or, conversely, refusing to talk about it at all. Both are coping mechanisms—either trying to confess and get it out of your head, or trying to suppress it. Neither truly works for long. “I keep reliving it” captures how moral injury refuses to stay in the past. The moral pain replays in high definition, making it hard to ever really feel like you’ve left that moment behind.

8. “I can’t forgive myself.”

Perhaps one of the heaviest burdens of moral injury is the inability to forgive yourself. You might believe what you did (or failed to do) is unforgivable. In your heart, you pass a harsh sentence on yourself: guilty for life. Emotionally, this sign is characterized by intense shame and self-condemnation. Shame is that feeling that you’re not just someone who did something bad, but that you are bad to the core. You might feel unworthy of love or happiness—as if you don’t deserve good things anymore. This can spiral into thoughts like “I’m beyond redemption” or “There’s no fixing me.” Behaviorally, carrying this shame often leads to self-punishment. You might sabotage relationships, push away people who care about you, or deprive yourself of opportunities because deep down you feel you should suffer. You isolate yourself not only because you feel others can’t understand, but because you think you don’t deserve their understanding. In some cases, people turn to alcohol or reckless behavior almost as a subconscious penance—hurting themselves because they’re hurting inside. “I can’t forgive myself” is a wall that blocks out healing. It’s as if you’re keeping yourself in an emotional prison. Yet remember this: The very fact that you feel this much remorse shows that your conscience is alive and good. You are not a monster; you are a good person who feels horrible about a bad situation. Understanding that can be the first crack in that wall, a sign that maybe, just maybe, you can learn to show yourself a little mercy down the road. A simple mantra can help begin this journey: ‘Because I judged, I care.’ By repeating this, you acknowledge that your remorse comes from a place of compassion, a reminder that feeling deeply is part of your strength.

9. “I’m alone in this.”

Moral injury can be an isolating wound. You feel cut off from others, convinced that no one else could possibly understand the hell in your head. You might be surrounded by family, friends, or fellow veterans, yet still feel utterly alone. Emotionally, this sign presents as a deep sense of loneliness and alienation. You carry a secret shame or sorrow, and that makes you feel different from everyone else. They all seem fine, unaware of the moral nightmare you’re carrying. You might also fear judgment—“If I told them what I did, or what happened, they’d hate me.” So you stay quiet, further trapping yourself in solitude. Behaviorally, this often leads to social withdrawal. You cancel plans, avoid group gatherings, or, if you do show up, you keep conversations superficial. You stop talking to the friends from “before” because you assume you’re not the same person now, and they won’t relate. Perhaps you gravitate only to others who have been through similar experiences (other vets, other first responders), yet even with them, you might not open up fully—there’s that voice saying “It’s just me. I’m the broken one.” This isolation can create a feedback loop: the more you pull away, the more alone and abnormal you feel, which then makes you pull away even further. It’s crucial to recognize this false sense of alienation. Moral injury wants you to believe you’re the only one, but in reality, many carry these unseen wounds. You are not alone, and you don’t have to face this pain in isolation.

10. “I don’t know what’s right or wrong anymore.”

Before, life had clear lines. Your moral compass pointed North, and you knew right from wrong. Now, after everything, that compass is spinning in confusion. This is the sign of moral disorientation. You might find yourself questioning everything you used to believe. Actions that seemed unquestionably right or wrong now sit in a grey zone. Perhaps you used to believe that “good guys always do good things”, and then you saw good people (including yourself) doing bad things for what seemed like good reasons. Now you’re left wondering, “Does being good even matter? Is there even such a thing as a truly good choice?” Emotionally, this is deeply unsettling. It’s like the floor of your ethical world has dropped out, leaving you anxious and uncertain about your own judgment. You may feel distrustful of your own moral instincts—afraid to make decisions because you’re not sure you’ll do the “right” thing anymore. Behaviorally, this might manifest as indecision and a tendency to avoid responsibility. For example, a morally injured nurse might avoid taking charge in critical situations because they’re plagued with doubt from past moral conflicts. Or a veteran might disengage from civic or community duties they once valued, thinking, “It’s all corrupt anyway.” In some cases, people swing to an extreme black-and-white thinking as a coping mechanism—clinging to rigid moral rules because their internal guide is shaken. “I don’t know what’s right or wrong anymore” is a sign that your ethical framework has been rocked by trauma. It’s scary, but it also means you’re grappling honestly with what happened. In time, many people do rebuild their moral compass—sometimes a bit differently than before, but with the wisdom of lived experience.

A Path Toward Healing

If you saw yourself in these signs, hear me clearly:

You are not ruined.

You are not beyond repair.

Feeling lost, angry, ashamed, or spiritually disoriented doesn’t make you weak at all. It makes you honest. Moral injury has a way of convincing us that we are broken at the core, that something inside us is too dark or too damaged to ever be redeemed. But that voice in your head, the one that calls you a failure, a burden, a disappointment, is not the truth.

It’s the echo of pain you never had the language to describe.

What you’re feeling, guilt that won’t let go, shame that eats at your identity, anger you don’t know how to aim, the numbness you use to survive, isn’t a character flaw. It’s a moral wound. It means your conscience is still alive. It means you still care about right and wrong, even if you don’t know what “right” looks like anymore.

And that alone makes you salvageable.

Healing moral injury isn’t simple, and it isn’t quick.

But it is possible.

I’ve done it.

I am still doing it.

It begins with naming the wound and telling the truth, first to yourself, then to someone you trust. Recovery isn’t about erasing the past or pretending you’re “fine”. It’s about learning to carry your story without letting it crush you. It’s about separating who you are from what you lived through. It’s about reclaiming the strengths you buried under shame.

You don’t have to figure that out alone. There’s a whole community, people like you who feel too much, think too deeply, rage too quietly, and blame themselves too harshly, who’ve walked through their own moral fire and found a way out.

Veterans, warriors, first responders, nurses, neurodivergent minds, sons and daughters carrying father and mother-wounds, young men and women who were told to “man up” or “suck it up” when what they needed was a mentor. They’re here. And they get it. We get it.

Just by reading this, you’ve taken a step most people never take: you’ve allowed yourself to see the pain instead of hiding from it.

If any part of this hits you, stand with us at Wayward Purpose. Subscribe for stories, tools, guidance, and language that will help you make sense of what happened to you and who you are becoming. This is a place for those like you who are tired of drifting, tired of pretending, tired of carrying the weight alone.

We’re building Wayward Purpose to help those who want to do the hard work to turn moral injury into moral leadership through faith, discipline, and direction.

You don’t have to carry this alone anymore.

You’re not hopeless.

You’re not done.

And you don’t have to heal in silence.

We got you.